[This post is part of an ongoing Profile of a Contemporary Conduit series on Jadaliyya that seeks to highlight distinct voices primarily in and from the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia.]

Jadaliyya (J): What motivated you to start blogging?

Mona Kareem (MK): I blogged anonymously starting from 2006 about Kuwaiti politics and minorities in Kuwait. The uprisings motivated me to put my literary and journalistic writings together in a blog, considering the lack of scholarship and reporting on the Gulf region. The stateless minority in Kuwait that I come from did not have any access to media or public exposure, except through blogging and social media.

J: What topics/themes do you cover and why?

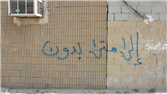

MK: I am mostly interested in the issues of minorities in the Gulf. I believe the struggle of those communities is even harder because of how much money Gulf regimes spend on media outlets and organizations to protect their image and further suppress any possibility for us to be heard. The stateless, or the Bidūn, exist in every Gulf country and are denied any right or documentation. Their struggle is against the dominant class and its culture. In Kuwait, the urban, rich class has been the biggest enemy of the tribal, stateless class. In other Gulf countries, the clash is constructed differently, but is of the same nature.

J: From your perspective, how does blogging fit into the wider scope of alternative media?

MK: Blogging has been an alternative source of writing in the Middle East since the war on Iraq. Everyone was looking for the other side of the story, the voice of the insider. Since then, a whole generation has been able to speak through blogging about their concerns – whether regarding politics in general or specific causes against inequality, censorship, etc. The value of blogging to me comes from its nature of being political and opinionated. Media everywhere chews on the discourse of neutrality when in reality, each of them follow a certain agenda. It is in blogging that we can see events narrated and discussed without pretending or claiming to hold ultimate truth in its content.

J: What obstacles have you faced writing about the Bidūn?

MK: It was a completely alien topic when the uprisings first started. Many times, I felt stuck explaining the very basic foundations of the issue and trying to analyze the irrational policies of the government for others. This has changed lately as the Bidūn continue to protest, use social media, and try to expose the oppression practiced against them. On a personal level, my family’s security is always at risk and my chance to have any documents renewed is poor. From experience, speaking about that in detail is also not a possibility, as it only brings more risks to those related to me.

J: How has the Kuwaiti government handled dissent within the past two years?

MK: Very badly. Many of us were hoping to see a more tolerant reaction from authorities, but the citizens and the stateless who continue to protest face intimidation in the region far too much. In 2011, the prime minister was changed and a change in the political system seemed very possible. Right after, the regime made a sudden turn and abused the system to push forward a puppet parliament and to prepare for changes in the constitution that would only lead to a more authoritarian system. This struggle resulted in having more than four hundred people on trial for political reasons since 2011, including protesters, Twitter users, and bloggers.

J: How do you respond to claims that Kuwait exemplifies the most “progressive” or “democratic” government system in the Gulf?

MK: This claim is outrageous, as it serves the interest of the authorities. The situation is only better comparatively. But can a regime be “democratic” and “progressive” because it is neighbored by a bloody dictatorship in Bahrain and a horrific theocracy in Saudi Arabia? Kuwait was ahead of the rest when it was open for all during the 60s and the 70s. Right now, it is just another oppressive Gulf emirate where free speech is violated normally, migrant workers are enslaved, the stateless are dehumanized, and women are only said to be equal because they got to vote in a parliament that has lost its meaning.

[Mona Kareem tweets at @monakareem and blogs at Mona Kareem.]

![[Image of Mona Kareem.]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/ScreenShot2013-03-21at8.23.37PM.png.jpg)